Hannah Hoover — “Narrating Local, Native Histories from Legacy Collections at the Brays Island Nature Center in South Carolina”

In November of 2022, I visited the Brays Island Nature Center near where I live in Beaufort, South Carolina. In addition to educating the many owners of the Brays Island Plantation, a 5500-acre residential and sporting community, the nature center stores archaeological collections recovered from the property in 1988 and 1989. Upon learning this, I wondered if these collections contained materials relevant for my dissertation. By using archaeological data, my research explores the daily lives of the Yamasee, a powerful Native nation who moved to the region at the turn of the 18th century. Three known Yamasee towns once surrounded Brays Island. Might there be another town on the property? Could I identify this town through the Brays Island legacy collections?

What I thought would be only a few visits to look for Yamasee artifacts turned into a several-months project, and an opportunity to complete the internship requirement for the Museum Studies Graduate Certificate Program. Upon my first visit to the Brays Island Nature Center, I learned that these over-30-year-old legacy collections were stored in 12 degrading cardboard boxes with largely uncatalogued artifacts still in their original excavation bags. As the nature center’s naturalist watched, I lifted a bag out of the first box. The bottom promptly busted, and several ceramic sherds fell to the ground. As I hurried to pick up the artifacts and assess any damage, the naturalist brought me a plastic sandwich bag as a replacement. I then picked up another bag, it also broke, and ceramics once more fell to the ground. By this point, the naturalist seemed embarrassed by the state of the collections and conveyed a “do you even know what you are doing” glance in my direction.

The answer was no, I did not know what I was doing. And many archaeologists often do not know what they are doing when first approaching a legacy collection. In archaeology, ‘legacy collection’ refers to collected objects and materials where no museum or repository was formally designated for long-term curation. The legacy collections of Brays Island were recovered during federally mandated cultural resource management (CRM). Under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), all planned development on federal properties, developments accepting federal funding, or developments that require federal permitting must first assess the property for cultural resources of significance. These may include archaeological sites, historic homes, or other landmarks potentially eligible for inclusion to the National Register of Historic Places. The ultimate curation of materials recovered by CRM projects is left to the discretion of the developer or property owners. Sometimes collections are stored in perpetuity by a state repository; but in other cases, especially with collections recovered during the 20th century, artifacts and documentation may be dispersed across several repositories or stored in closets, basements, and sheds often without an inventory or ideal preservation conditions.

While every legacy collection has its own unique history of creation and curation, many are inaccessible to scholars because of poor preservation, poor documentation, or little knowledge of their existence and place of storage. Such practices almost certainly shape what archaeologists do and don’t know about the past, and often lead to more academic excavations than might be needed if legacy collections were considered. This perpetuates the ‘curation crises’ experienced by many museums around the world. In the Southeast US, a region that has experienced centuries of Indigenous land dispossession, the obscurity of legacy collections also perpetuates a general lack of public knowledge and engagement with local Native histories. This erases deep-time Indigenous ties to land and hinders modern movements for Indigenous self-determination.

In this broader context, I was eager to work with the Brays Island legacy collections for several reasons. While I still hoped to identify evidence of Yamasee settlement, I planned to rebag and catalog each site collection along the way. I also wanted to digitize records and create an interactive database accessible to nature center staff and property owners. The focus of these efforts was primarily to share new information about the Indigenous histories of Brays Island which stretch several thousand years. While these goals were variably met, and some are still ongoing, I learned innumerable lessons about working with legacy collections. This blog post is one attempt to distill my experiences.

Location of the Brays Island Plantation property today near 18th century Yamasee sites in South Carolina.

A History of Archaeology on Brays Island

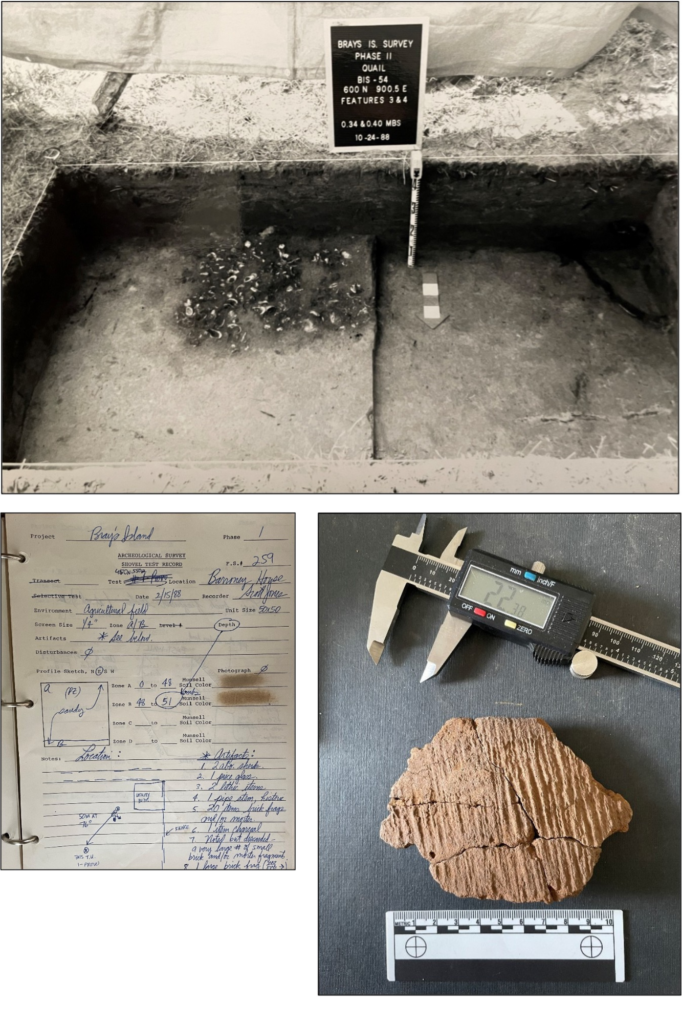

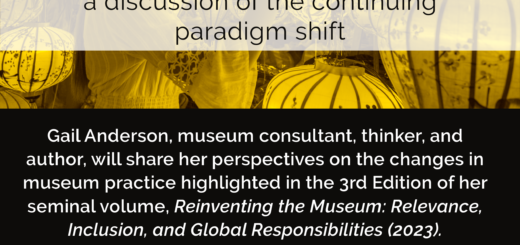

Before residential construction began in 1988, the newly formed Brays Island Colony Inc. contracted Florida Archaeological Services (FAS) to assess the cultural resources of a large 2500-acre tract. Over the course of a year and a half of research, FAS identified 48 archaeological sites, 19 of which are currently potentially eligible or eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. Overall, this work produced a large number of artifacts, ecofacts (like plant and animal remains), photographs, field paperwork, and maps. Most of these materials have been stored at the Brays Island Nature Center for the past 20 years.

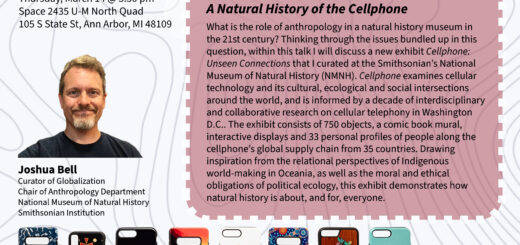

In January 2023, I began working my way through artifact bags from each of the 48 sites identified by FAS. In many cases, artifacts were stored in their original (brown paper lunch bag) field collection bag or in degrading plastic bags. Following state curation standards, I rebagged artifacts in 4-mil curation quality plastic bags and assigned catalog numbers. This required identifying artifacts of a wide range of types, including Native American and European pottery, stone tools, glass, brick, and all sorts of corroded metals. Using ArcGIS and a report written by FAS in 2000, I georeferenced the location of each excavation unit or field surveyed so that artifacts could be spatially visualized and compared. In many cases, this required sorting through original field documentation and photographs. I later scanned these documents and organized them by site, excavation, and spatial context.

This process was intended to bring the collections to modern standards, with the goal of long-term curation at an archaeological repository (like the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology). As an added benefit, the process ensures that archaeologists will be more easily able to reconstruct the work of FAS and form research questions that will reuse these collections. To this end, I am excited to explore a variety of online repositories where I may share these archaeological data, like tDAR and Open Context. I am in the process of creating an interactive StoryMap hosted by ArcGIS Online to be viewed by visitors to the Brays Island Nature Center. Ideally, each archaeological site will be displayed as part of broader property tracts or neighborhoods (specific locations will not be publicly accessible), with a brief description of their history and interesting artifacts. In the future, I also hope to assist with redesigning a small exhibit space within the Nature Center.

Narrating Local Native Histories

While working my way through the collections, I was struck by the several thousand years of local history cumulatively embodied by these archaeological sites. I noted at least three time periods well-represented by the collections. I provide brief descriptions below to emphasize both the utility legacy collections hold for filling gaps in archaeological inquiry but also their general value for narrating local histories for educational purposes.

The earliest cultural period significantly represented by Brays Island archaeological sites is the Early Woodland (2500 BCE-100BC). Indigenous societies were seasonally mobile and harvested shellfish and other wetland resources. They also created ceramic technologies for the first time. This first pottery tradition, the Stallings series, was fiber-tempered and formed shallow and large wide-mouthed bowls. This technology quickly spread to other regions across the Eastern Woodlands and signaled a significant shift in communities’ settlement and food practices. There are several Brays Island sites with Stallings phase pottery. At least two sites also have clay balls, what some scholars believe was an intermediary technology that led to the creation of ceramic vessels. They were likely used as a thermal conduit for accelerating the boiling of water. In most archaeological contexts, clay balls are found broken from thermal shock. Some clay balls recovered from Brays Island are intact and present interesting questions about local cooking practices.

During the transition from the Early Woodland to Middle Woodland periods (1000 BCE – 300 CE), we begin to see Indigenous communities settle into more sedentary or semi-sedentary lifestyles. Across the southeast, villages emerge for the first time. This leads to the development of new technologies and innovative horticultural practices. Early villages are some of the most difficult archaeological phases of human precolonial history to locate in the Southeast. Structures built with bent-pole architecture and without subterranean basins or wall trench supports leave only small (~8cm) soil discolorations of post molds. Along the southern Atlantic Coast, where sandy soils produce little organic growth and thus shallow cultural deposits, there are few published examples of Middle Woodland structures. Excitingly, Brays Island has at least two archaeological sites with evidence of multiple household structures and intact cultural features like storage and trash pits. These are exceptional examples of village life with the potential to address a wide variety of research questions often inaccessible to scholars.

The last major cultural period is the antebellum period when much of the property was divided into several plantations. During this time, colonoware pottery––made by enslaved Africans and Native Americans with forms and styles borrowed from several ceramic traditions––was used on plantations across the Atlantic Coast. Archaeologists have long debated where colonoware first appeared and how it spread so rapidly across a massive geographic area. Colonoware was recovered at some archaeological sites on Brays Island. Later, in the 19th century, at least two homesteads were owned by free people of color as recorded in census records. One archaeological site may be evidence of these homesteads. There are also four historic African American cemeteries that saw continued use from the antebellum period into the post-Civil-War Reconstruction era. Some families continue to bury family members in one of these cemeteries.

Ultimately, I identified early 18th century Yamasee artifacts but these were, of course, from two bags without provenience information. While I was unable to identify a new Yamasee town on Brays Island, the cumulative product of this work revealed new and exciting information about local histories.

Community Engagement

The process of this work provided a variety of opportunities for community engagement. I gave a public lecture to Brays Island residents and tagged along on an annual wagon-ride history tour hosted by the center’s naturalist, Jake Zadik. I also led local residents in new excavations of a site where a boat shed will soon be constructed. I would like to think that many owners are now more familiar with archaeology, the histories of this landscape, and the importance of investing in and preserving cultural sites.

Cultivating this kind of community interest is vital in a region where a significant portion of land is privately owned and/or actively being developed. This means that Indigenous cultural heritage is inaccessible to most Indigenous communities seeking to reconnect or legally affirm their rights to their ancestral homelands and cultural patrimony. Re-curating legacy collections, collating disparate threads of excavation records, and sharing these data is an important way for archaeologists to apply their skill sets towards Indigenous-led efforts in South Carolina and beyond.