Christiana Sinacola — “Conversations from the Herbarium”

“What’s your favorite plant?”

I think maybe I should have anticipated this question. From my seat across the small conference room, I begin to feel nervous for the first time almost a half hour into the job interview. Opposite me sit three of the Herbarium staff, each with a few sheets of questions now decorated with notes from our conversation that I fear will soon come to an unceremonious end. My knowledge of Latin is woefully inadequate, my knowledge of plant taxonomy even worse. What if I name a stupid plant and they share a knowing glance before quietly crossing my name off of their list? All at once, I feel as if the entire interview is riding on this question.

What is my favorite plant?

When I first applied for the job at the Herbarium through the Museum Studies Program, I didn’t quite know what to expect. The Research Museum Center (RMC)

is located about 15 minutes off campus at the end of a long circular driveway of sorts: like a really long and mysterious house at the back of a cul-de-sac. You wouldn’t know from looking at it, but this building houses thousands of specimen cabinets and millions of plants and fungi (and some incredibly fascinating insects – or terrifying depending on your general feelings about insects).

On my first time there, I was led through the cubicle workstations, past the packing and shipping room, down another hallway, through a small library (of books, not plants), through another room of looming camera setups, into a huge warehouse-that-is-not-called-a-warehouse-please-do-not-refer-to-it-as-a-warehouse. I saw ever-receding rows of file cabinets filled with folders and folders of sheets and sheets of pressed plants. These are the archives.

I told people I worked at the Herbarium, to which they would always respond, “What is that?” I began to anticipate this question and instead described it in the way that was most immediately familiar to me. “It’s like a giant plant library,” I would tell them. The comparison is apt. I’ve spent most of my life in libraries, and I’ve worked in a few as I got older, albeit always with books as the primary materials. But it was these two words that came to grace my work at the Herbarium in a charming new light. I’m an English major after all, libraries are my thing.

Libraries have catalogs, and the main chunk of my work at the Herbarium has been filling the digital catalog with images and information so that all of the specimens in the archive can be accessible online – specifically the specimens from the Eastern Hemisphere as a part of a National Science Foundation-funded digitization project. The full name of the project is “Bringing Asia to Digital Life: Mobilizing Underrepresented Asian Herbarium Collections in the US to Propel Biodiversity Discovery,” but we call it the “All Asia Project” for short. There are two goals at the Herbarium: 1) Make it findable. 2) Make it last forever. Digitizing and databasing the specimens helps accomplish both. The first thing I learned was the transcription process. From the genus and species name to the location where it was collected and the home from which they dug it (ad ripas fluminis juxta arborem), I have traveled across Asia in search of these plants.

And as I work, I am making discoveries. As part of my internship, I got to learn how we mount the new pressed plant specimens. Did you know that after the plant has been glued and dried under sandbags, we have to bend it to make sure that glue does its job? The first time I watched practiced hands ease the paper into a tight arc, I thought I was witnessing sacrilege. I had been taught to handle old specimens with care, whether that be books or art or artifacts or plants. I’ve seen specimens from 1832 and specimens partially crisped from what I later learned was smoke damage. To make it last forever, they say, do not touch. But that’s the wonder of working with new types of collections. Sometimes you must bend the rules.

After they are mounted and sorted, all of the specimens we eventually will transcribe must first be barcoded and photographed. At my imaging station, I move back and forth underneath this odd sort of praying mantis machine. With two extended lights for arms and an elevated camera for the head, I breeze through stacks of plant specimens under the watchful eye of a Canon. And sometimes, the watchful eye of a supervisor wanders over to teach me something wonderfully foreign.

“What are you working on now?”

I flip the cover of the folder to show the family name.

“Oh, Boraginaceae. Do you know about Boraginaceae?”

I admit I do not. I also admit that I may have misread it as “Boringinaceae” on accident.

“Well that’s the family with forget-me-nots.”

A few summers ago, I lived in a house with an abundance of forget-me-nots planted all around the edges of the yard. They’re small and bright, with flexible stems perfect for flower crowns. I collected them to press between book pages and slip into the back of my phone case. I think of how definitively not-boring I find forget-me-nots. I apologize to the Boraginaceae folders.

“What are you working on now?”

I flip the cover of the folder: Myrtaceae.

“Do you know about Myrtaceae?”

Nope.

“When you open the cabinet that holds all the Myrtaceae specimens, you’ll know. It smells.”

It smells?

“Myrtaceae has eucalyptus, cloves, and tea tree oil.”

I lean over the paper. Maybe I can smell something.

“What are you working on now?”

I flip the cover of the folder and point to where it says “Ericaceae.”

“Have you ever heard of the ghost pipe?”

I have not.

“Look it up, we have them in Michigan.”

They’re droopy and haunting and beautiful. Little hanging ghosts.

“We have some in the Herbarium.”

A pause.

“Would you like to see them?”

We go on an adventure.

One day, I made my own discovery. One of my final projects at the University is an English capstone thesis. Mine is all about fairy tales. When I started to work at the Herbarium, I never thought these two projects would collide.

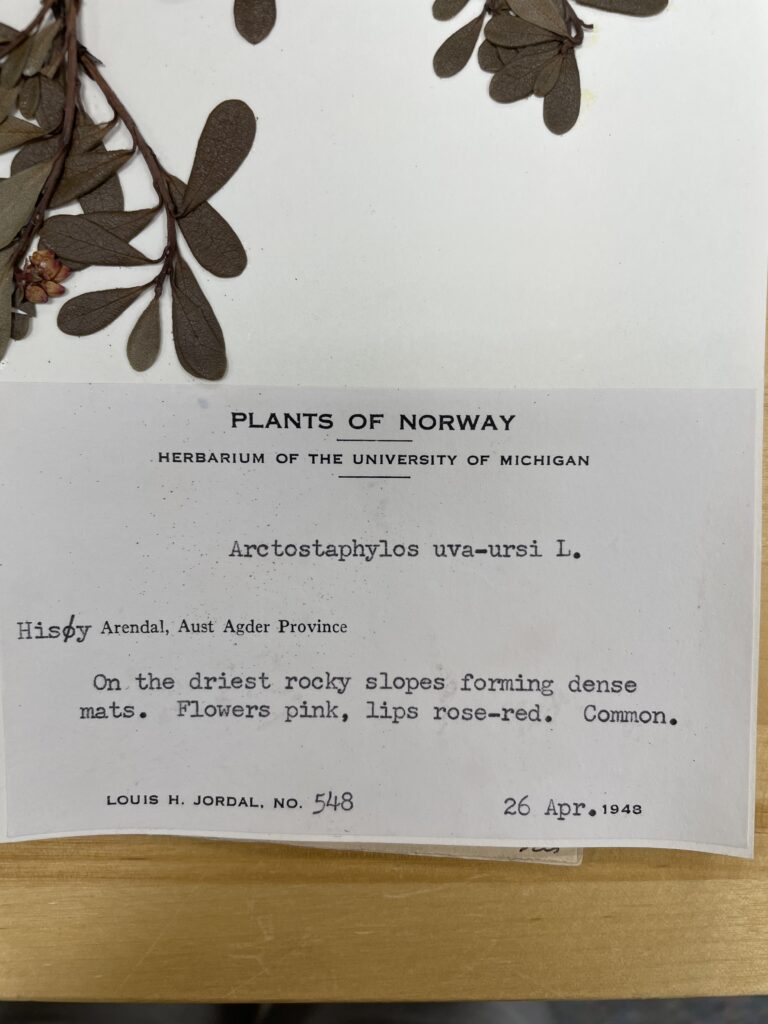

This is Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, also commonly known as Kinnikinnick or Red Bearberry. This particular plant is 75 years old, originally collected in Norway by Louis H. Jordal, and apparently is now extinct in Delaware.

Red Bearberry has small, teardrop-shaped evergreen leaves and bell-shaped flowers that ripen into red berries. What is important, however, is the label.

On the official typewritten label of this specimen, Jordal gives the following description: “Flowers pink, lips rose-red.”

The term “lips” is a technical descriptor for that distinct curl at the petal’s edge. The label itself and my encounter with it felt straight out of a fairy tale, and it only got more delightful when I looked up the specimen later.

The specimen I showed before is very old, very dry, and very brown. Here’s an image of the plant when it’s alive which better illustrates what Jordal so precisely termed the “lips.” Arctostaphylos uva-ursi has rosy lips any evil queen might envy.

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi photo by Sarah Gregg on Flickr. Free to share and use under creative commons copyright.

Gregg, Sarah. Arctostaphylos uva-ursi MOD512-S052. Photograph. Flickr. November 22, 2015.

https://live.staticflickr.com/3826/10347089376_cf97674f89.jpg.

I have transcribed over 3,000 labels and imaged over 20,000 specimens. At the time of writing this, there are no more “All Asia” materials to image. My knowledge of Latin is marginally improved. My knowledge of plant taxonomy even more so.

“I don’t want you to think we forgot. We still haven’t heard your answer; what’s your favorite plant?”

“Well, I’ve always liked dandelions.”

Special thanks to my three interviewers and supervisors – Brad Ruhfel who told me about forget-me-nots and ghost pipes, Kyle Lough who showed me how everything works and answered lots of questions, and Aly Baumgartner who provided me with endless fun facts.

All photos are my own courtesy of the University of Michigan Herbarium or free-to-use images sourced from the internet.

Christiana Sinacola

Christiana Sinacola is an English major at the University of Michigan with minors in both Digital Studies and Museum Studies. Her research focuses on the lasting influence of stories across cultures, geographies, generations, and media. Focusing on how and why we tell certain stories reveals the groups who have bolstered culture across the centuries and those who have been obscured. She always has time for a good book, a dance, or a meal with friends and family.