Alice Register — “Can We Still Hear the Bankoku Shinryō Bell?”

I have long dreamed of pursuing a research project in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, where my academic research interests lie and where I also have deep personal connections. However, with funding constraints and coronavirus pandemic realities, I knew that this would probably remain just that—a desired but unattainable dream. So, when a few years later, in October 2022, I found myself living in Okinawa, and the Okinawa Churashima Foundation (沖縄美ら島財団, Okinawa Churashima Zaidan) offered me an opportunity to work with them as a Museum Studies Intern at the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum (沖縄県立博物館・美術館, Okinawa Kenritsu Hakubutsukan・Bijutsukan), I could hardly believe it. Dreams sometimes really do come true!

The Okinawa Churashima Foundation + The Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum: A Brief Overview

My host organization, the Okinawa Churashima Foundation, was originally formed in 1976 to create a national park on the former site of the Ocean Expo ‘75—a World’s Fair commemorating Okinawa’s return to Japan after 27 years of United States’ administration. The Foundation has significantly expanded its activities in the last 40+ years, including engaging in research and educational outreach activities. It also operates and manages sites of high public interest and tourist activity throughout Okinawa Prefecture. In addition to my internship site—the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum—the Okinawa Churashima Foundation (hereafter OCF) also manages the Ocean Expo Park, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium, Shurijo Castle Park, and the Nago Prefectural Youth Center.

One of the key sites managed by OCF, the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum is located in Naha City, capital of Okinawa Prefecture. This museum is comprised of two distinct museums housed within one building—a natural, historical, and cultural museum (博物館・hakubutsu-kan) and an art museum (美術館・bijutsu-kan).

It holds the largest collection of Okinawa-related items in the prefecture, with over 94,000 objects and 3,700 pieces of artwork in its collections. It maintains its established permanent exhibits as well as develops a robust series of special and rotating exhibits throughout the year. Built in its current location in 2007, the year 2023 marks the museum’s 77th year.

Identifying Priorities: Discerning Internship Duties

At my initial interview with OCF, I wanted to arrive with no preconceived notions of what my internship duties might be. I wanted this to be identified and assigned by OCF, based on their specific needs and the ways that OCF thought that I could best support them in their efforts. What rose quickly to the top of our conversations was the effect that the coronavirus pandemic had on international and domestic museum visitors. The museum experienced a 76% decrease in visitor attendance over the course of the pandemic. Therefore, one of the outcomes of our initial discussion was that I could assist in a concerted effort to restore visitor numbers by supporting public outreach efforts and strategizing how best to design materials to reach international audiences and appeal to English-speakers.

Over the course of my internship, and with travel restrictions in Japan starting to ease in late 2022, museum attendance has recovered and even surpassed pre-pandemic numbers for international visitors to the museum. This underscored even further the need for multilingual support and efforts to make the museum more accessible to visitors who are not fluent in Japanese. Providing multilingual support—focusing most of my efforts on the localization, translation, and proofreading of outreach materials (textual, visual, video, and auditory) from Japanese to English—therefore accounted for approximately 70% of my internship duties. The remaining 30% of my duties included providing general assistance for whatever was identified as being prioritized within the flow of museum operations; e.g., staffing educational outreach and community engagement events, strategizing about wayfinding guidance, assisting with the physical set up of event and exhibit gallery spaces, recording English audio, answering English-speaking visitors’ inquiries, and providing general support for museum visitor-services staff regarding English language communication best practices.

The Bankoku Shinryō “Bridge Between Nations” Bell

As part of my work to provide linguistic support and engage English-speaking audiences, I assisted with public outreach around the Former Shurijo Castle Seiden (Main Hall) Bell (旧首里城正殿鐘, Kyū Shuri-jō Seiden (no) kane). More commonly known as the Bankoku Shinryō no Kane “Bridge Between Nations” Bell (万国津梁の鐘), this bell is part of the museum’s permanent exhibit.

A message engraved on the bell proudly proclaims that the people of the Ryukyu Kingdom—a kingdom once at the center of a powerful and vast trade network—acted as a “bridge” connecting many nations. (Okinawa Prefecture was once the independent Ryukyu Kingdom before it was abolished and incorporated into Japan in 1879 during the Meiji Period.) This bronze bell, commissioned by the sixth king of the first Sho Dynasty (1406-1469) of the Ryukyu Kingdom, originally hung in front of the main hall (seiden) of the Shuri Castle palace.

The Shuri Castle is a highly significant historical and cultural site in Okinawa, and the bell that used to hang in its main hall “symbolizes a prosperous era of the Ryukyu Kingdom” (text quoted from current Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum pamphlet). Once the center of the political power of the Ryukyu Kingdom before annexation to Japan, Shuri Castle was almost entirely destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa in World War II.

A careful reconstruction based on archival architectural and historical documents was completed in 1992, and it was designated a World Heritage Site in 2000. It then again underwent devastating damage and was mostly destroyed by a fire in 2019. It is currently being restored again, with estimated completion in autumn, 2026.

I was asked to consider how to best communicate the historical significance of the Seiden Bell to audiences unaware of Okinawan history and how, through proper contextualization, I could increase understanding and interest and draw international visitors to the museum. Through showcasing important historical objects like the Seiden Bell, the OCF hopes to not only add to the enjoyment of tourists and international visitors, but also to deepen their travel experience, and to instill a meaningful, lasting understanding of Okinawa. The goal is to utilize the museum venue and the objects within its collections as a means to tell important stories, engage visitors in meaningful dialogue, and communicate a message of restoration and peace.

My work with the “Bridge Between Nations” Seiden Bell is ongoing. So far, towards this effort, I have created English subtitles for a YouTube animation, telling the Story of the Bell. This video is designed to be played on a loop in the museum lobby, prefectural library, and other public areas.

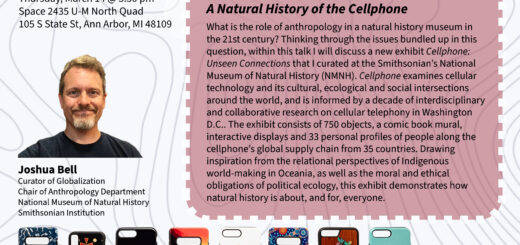

I am also working with museum curators and designers to develop textual content and design the visual layout for an original English language pamphlet detailing the bell’s story, historical background, significance, and appeal. The image to the right shows the Bon-chan character designed to promote the Bankoku Shinryō “Bridge Between Nations” Bell Project with explanatory booklet, the Kai Tai Bon Syo – 解体梵鐘.

More Questions than Answers

My efforts to communicate the story of the bell bring up many research questions that I am still contending with, largely centering around what it means to provide ethical and effective multilingual support in the museum setting. Translation and localization are not straightforward, neutral processes where there is direct correspondence between words in the source and target languages.

How can this bell be adequately contextualized so as to be “heard” and made intelligible to a wide array of visitors? Furthermore, how do we localize a museum—not just its discrete and more tangible products like text and visual layout that are on a two-dimensional plane—but also its 3-dimensional spaces and the embodied experience of learning as impacted by spatial design, lighting, auditory, visual, and other forms of sensation? How do we accommodate differing cultural senses of privacy, space, and visual cues? What are the best practices for translation and localization from a source language (in this instance, the Ryukyuan languages and Japanese) to develop effective bilingual or multilingual exhibit labels? Whose voice is advanced? What design and naming conventions should be used, and what kinds of knowledge are we privileging? How do we ethically translate and localize vast bodies of knowledge and adequately contextualize content so that it can at least start to approximate some kind of meaningful point of departure for the museum visitor’s journey towards mutual understanding?

Finally, how do we accommodate and negotiate differing understandings of history—especially contested histories within the Okinawan context? I don’t have answers to these questions yet, but I continue to develop and refine my understanding as my internship duties conclude. All of these questions remain at the forefront of my mind and directly guide and inform my efforts, especially as I work on finalizing the visual layout and design, as well as content development, for the English language pamphlet.

Can We Still Hear the Bankoku Shinryō Bell?

Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost prefecture, consists of 160 inhabited and uninhabited islands in the Ryukyu Archipelago. Once the independent Ryukyu Kingdom, Okinawa has long occupied a unique geopolitical position throughout history and in the “national-cultural-imaginary” of Japan (see Marilyn Ivy, Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan). While being small, Okinawa has a mighty, worldwide reach. Now standing at the nexus of major world powers in the “Pacific Arena”, it is in the news more than ever, especially as tensions continue to mount with the impending push to proceed with building a new US Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) installation in Henoko Bay despite resistance and protests by many Okinawan people. The legacy of Okinawa’s unique position throughout history has implications that continue to persist, having tangible influences on the daily lives of Okinawan residents and on the lives of everyone with connections to Okinawa to this very day.

This worldwide reach provokes one final question: Can we “hear” the “Bridge Between Nations” Bell and its appeal for peace today? Can we still hear its ring? What does it take to be made truly “legible” and truly “heard”? Can a bridge be established between Okinawan residents on the main island of Okinawa and a wide variety of people, including (but certainly not limited to) these visitors that I see in the museum:

- visitors from other islands within Okinawa Prefecture who have their own distinct

historical relationship to the main island; - domestic tourists from other prefectures in Japan;

- Japanese citizens originally from places other than Okinawa who are now living in Okinawa for study or work;

- US government and military personnel, many of whom have established multigenerational connections with the island;

- international residents who are in Okinawa for study or work;

- tourists from countries across the globe seeking a “tropical” getaway or scuba diving holiday;

- members of Okinawan diaspora communities in Brazil, Hawaii, and elsewhere.

Ancient Bell Still Resonant

I firmly believe that this ancient bell is relevant (and resonant) to this day. Meaningful dialogue and exchange are needed now more than ever. The Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum, housing its precious collections that bear witness to the ever-evolving Ryukyu-Okinawa, is a powerful place to negotiate and address the questions about ethics, translation, localization, accessibility, inclusivity, and democracy raised above. The museum can serve as a common meeting ground for various users to come together and establish some form of productive dialogue in an effort to promote understanding, mutual respect, and peace. I am forever thankful to the dynamic museum professionals at the Okinawa Churashima Foundation and the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum who have given me this precious opportunity to engage with these important questions, and who have taught me so much.

Alice Register

Alice Register ardently believes that visual storytelling and good design can serve as powerful agents of insight, change, and empowerment. She is motivated to explore the ways in which the ethical application of visual technologies can be used to advance multiple visions and promote understanding and dialogue across cultural and political boundaries. Alice has a background in studio art, digital media, social work, performance, ethnography, translation, and teaching. Prior to pursuing Museum Studies, she graduated with an MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan’s Center for Japanese Studies (CJS). Her MA thesis examined the politics of visual representation within the Okinawan context. While a student at CJS, she also had the opportunity to work with the UM Hatcher Graduate Library’s Japanese Studies Librarian and the Digital Pedagogy Librarian as a digital curation assistant for the Japan Constitution Slides (Jinken Sengen, 人権宣言) —part of the Alfred Hussey historical papers housed within the University of Michigan Special Collections.