Eimeel Castillo – “Accessibility in Museums: Thinking Outside the (Polyglot) Box”

July 3, 2022: It was a hot Sunday afternoon in July, and I was at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The crowds emerged from everywhere as this year’s Fourth of July and Folklife Fest coincided. The buzzing atmosphere reminded me that I was at the heart of American museological practice. My mission: to visit one exhibit and to test their multilingual accessibility kit for my internship.

The building door was wide-open at the Smithsonian Arts + Industries Building and there were so many people coming in and out that I felt like I was entering a mall or supermarket in the middle of a sale instead of a museum. It was the last few days of the FUTURES exhibit—the Smithsonian’s exhibition of future-themed art and design. As a native speaker of Spanish, I was curious and excited to experiment with their new Polyglot audio guide, and to engage with the process of translation and content design. I had never heard of such a feature: according to the Smithsonian’s website, the Polyglot is a new type of multilingual audio guide that comes in a cardboard box and is available in five languages. I approached the visitor counter and they informed me that, due to the high demand, the kits had overheated, the bottoms over-worn, and they had stopped working. To my disappointment, they did not even have samples that I could touch.

After I moved around the exhibit and walked away, I couldn’t help but think about the limits of accessibility when relying on technology. Was this a planning issue in which staff didn’t consider that the holiday weekend would lead to a larger number of visitors? Or was it instead a problem with the technical design of the Polyglot audio guides? Perhaps budget restrictions? In any case, the museum staff member whom I spoke to happened to be a bilingual Cuban American. He shared that he was the only Spanish speaker in the exhibit team and that, given the recent malfunctioning of the Polyglot audio guides, he had to explain entire sections of the exhibit to visitors who did not speak English. I kept thinking: is accessibility a question about human factors more than technological ones?

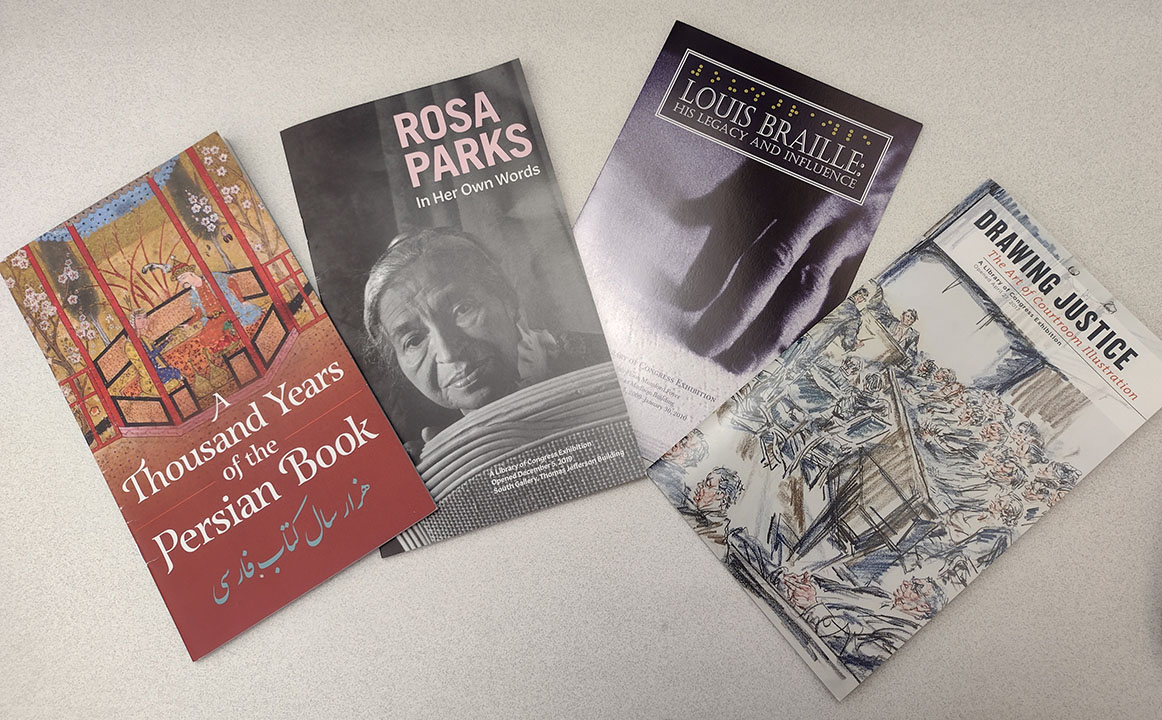

This was one of the several scouting trips I have carried out during my internship at the Library of Congress Exhibit Office this summer. This office is in charge of designing, planning and installing the multiple exhibits on display in different galleries at Thomas Jefferson’s building where thousands of visitors discover and learn about the holdings of the largest library in the world. The idea behind their new exhibit is to introduce audiences to the pillars of the institution’s ethos: to acquire, to preserve, and to divulge knowledge and cultural heritage. More importantly, the exhibit aims to promote a sense of connection with the public, a sense that the library is their space. With a biannual rotation of objects in display and a flexibility plan allowing for a change of topic every year-and-a-half, this exhibit also encourages audiences to donate collections to the library. The challenge is to make a variety of objects in different formats, from artist books, to story maps, to poems inscribed on a fabric in the form of a dress, as accessible as possible.

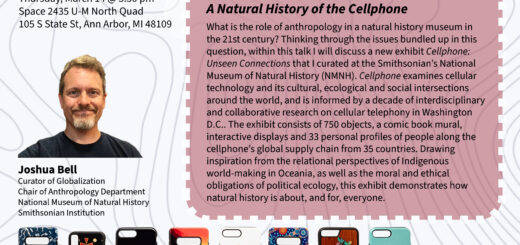

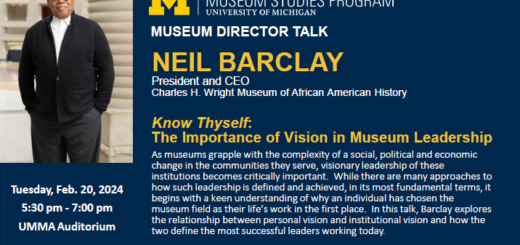

With this new exhibit in mind, my role as an intern is to support the office in their accessibility initiatives. One of my tasks is to investigate and test accessibility initiatives that sister exhibitions have taken. I have explored programming and services but also specific devices and apps. For instance, I visited the National Museum of American History’s new exhibit ¡Presente! A Latino History of the United States and National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Make Good the Promises: Reconstruction and Its Legacies. Once I explore the accessibility initiatives at such exhibits, I write an evaluation and provide feedback and reflections for the Library of Congress team to use.

So far, this internship has opened my eyes in many ways. Not only have I been lucky enough to be exposed to the rich and exciting museum scene that is Washington D.C., but it has helped me reflect upon the variety of ways in which museum practice in general, and the topic of accessibility in particular, is built upon close collaboration. Multidisciplinary teams of experts in design, pedagogy, curatorship, lighting and materials, budget and project management, conservation and so on, discuss and evaluate every detail during the planning phase. For example, a discussion of the speed and size of a video projection takes place with experts on media design, educators, and production experts to agree what is the best way to enhance the experience of visitors.

In the last months, I have been thinking a lot about the potential, as well the limits, of designing accessible interactions with museum objects: those that can become meaningful experiences without stealing aesthetic pleasures and the possibilities of explorations that all visitors deserve, regardless of their sensorial and linguistic abilities. I still remember the enthusiasm and sense of pride of the museum staff member at the Smithsonian Arts + Industries Building that Sunday. I could tell how important it was for him to share his cultural ties with visitors and to make them feel, just as he had been when he came from Cuba, welcomed. That human intentionality, in searching for a sense of belonging, might be at the heart of what we aspire in terms of accessibility in museums.

Eimeel Castillo

Eimeel Castillo is a graduate student in the joint program in History & Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Michigan. She received her M.A. in Latin American History at Tulane University in 2017. Originally from Nicaragua, Eimeel has experience as a university instructor in Managua. During the certificate in Museum Studies, she has become increasingly interested in the potential of museums to tell powerful historical narratives.