Benjamin Davis – “Digitizing the Museum: A Kiss of Death for Tourism?”

For a long time, the sole way that I was able to engage with the more renowned museums of the world (the Louvre, the Met, MoMA, etc.) was through online exhibitions and digitized archives. Even before the pandemic, I didn’t get out much because my family was not the most well-off to afford frequent vacations to far-off destinations. I never saw the reason to engage with museums in-person: why would I, if I could experience the exhibits in the comfort of my own home? This changed during my recent trip out to Colorado, and it was in the Denver Museum of Art that I realized the value of visiting physical museums.

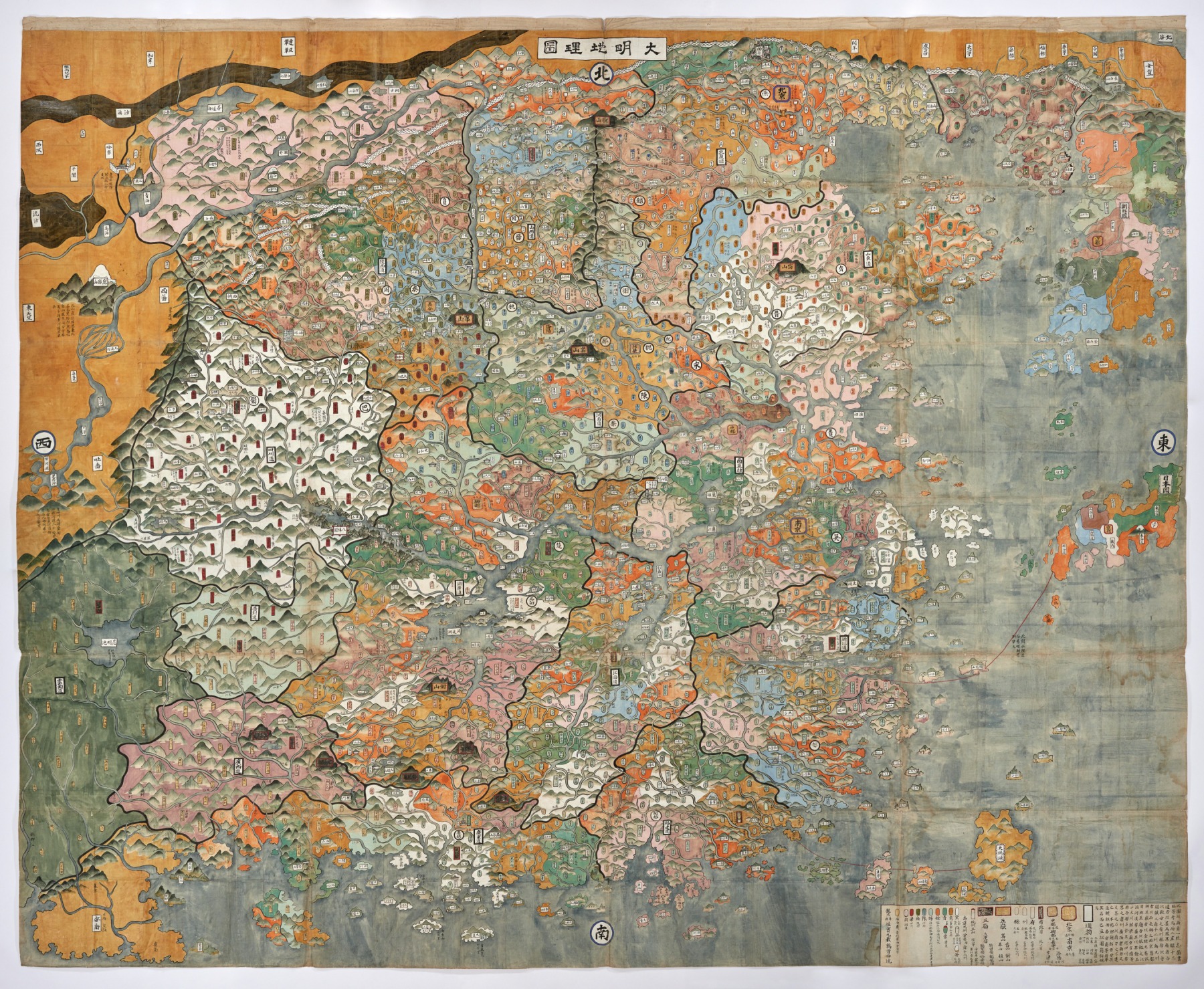

Having only visited one out-of-state museum (the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, on a middle-school trip to Washington, D.C.), I made sure I’d be visiting multiple museums during my Colorado trip. One of those places was the Denver Museum of Art. A sizable institution, the museum has objects ranging from Northwestern Native American art to Japanese prints. This was a solo venture, so I went through the galleries at my own leisure. The fifth floor of one of the buildings is dedicated to Asian art, and my keen interest in Asian culture and artwork led me to linger there. I stood in front of a lovely Japanese map titled “Geographical Map of Great Ming” produced in 1681.

The piece was immaculate. For being several centuries old, the condition of the map was stellar. It is a symbol of inter-society connection more than 300 years ago that resonates well with our current globalized world. I stayed there long enough that a docent approached me. We engaged in a riveting discussion about Japanese art and she gave me behind-the-scenes insight into how the map came into the hands of the museum and the difficulties that entailed its conservation. In that discussion, it hit me. This is why being in the physical space of the museum is crucial. There is so much from this conversation that I learned that I would never have been able to through digital means.

But even beyond conversations with docents, nothing can beat the sense of connection with a community and objects that comes with being in the physical space of the museum. In a way, the experience is a spiritual one. Being so close to the objects rather than viewing them through a screen elicits a unique response. Seeing the object in-person allows for a true understanding of its scale, vibrant coloring, and emotional impact. It sounds strange to word it in this way, but a sort of energy flows between the object and the visitor that cannot manifest through pixels on a screen. The sense of community is reminiscent of Durkheim’s classic concept of collective effervescence, a term to describe when a community comes together to communicate the same thought and perform the same behavior. A sense of exaltation can come over visitors as they all feast their eyes of masterpieces of art and culture. Docents can share their knowledge with museum goers as they waltz through the galleries. This cannot be done in the digitized museum.

Claiming that digitization will bring about the death of museum tourism, as I once thought, is absurd, and the effect of streaming on the cinema industry may hold a clue regarding the future of museums. When streaming came on the rise, many predicted that movie theaters would not survive. But streaming has been here for about a decade, and movie theaters are still around. People still come to movie theaters for an experience they cannot get on at home on the couch with a streaming service. The sanctity of the movie theater is surviving, and despite pandemic closures there persists a coexistence of streaming and theaters rather than triumph of one over the other. This is a good sign for museum tourism, and I believe we will see a similar coexistence as museums increasingly offer digital options.

Digitization can and indeed will increase without being a parasite that will eat up tourism and museums from the inside out. Rather, it will just exist as another form of engaging with museums. There are benefits to having digital collections that the public can engage with. They radically increase access to the museum’s collections for people who are unable to make the trek to the museum in-person—be that for socioeconomic reasons, disability, or if the world is plunged into a global pandemic. The traditional barriers of museums can be eroded through having a more fervent online presence. While a digital museum visit may not have the same impact as an in-person visit, observing a digital museum object can still be a meaningful experience. This can all be done without tarnishing the in-person experience of museum going.

Being within the museum without digital mediation still holds that lure that it always has since the inception of modern museums centuries ago. That spiritual connection with objects and the museum community will not die because of increased digital access. May digitization draw some members of the public away from visiting museums due to ease of access and the comfort of being in one’s home? Most likely. However, many, like myself, will come back again and again to the physical space of galleries to experience that sense of wonder, whimsy, and awe that can only be elicited through standing within an exhibition.

Benjamin Davis

Benjamin Davis is a senior at the University of Michigan hailing from Ortonville, Michigan studying Anthropology and Linguistics with minors in Museum Studies and Digital Studies. His interest in museum work resides in how museums can remain relevant during the digital age. When not in the world of academia, Ben spends his time catching up on the latest video games and finding the next great cup of joe in Ann Arbor.