Alexandria Rayburn – “Pink-Collared Computing: Examining Gendered Work in Museum Collections”

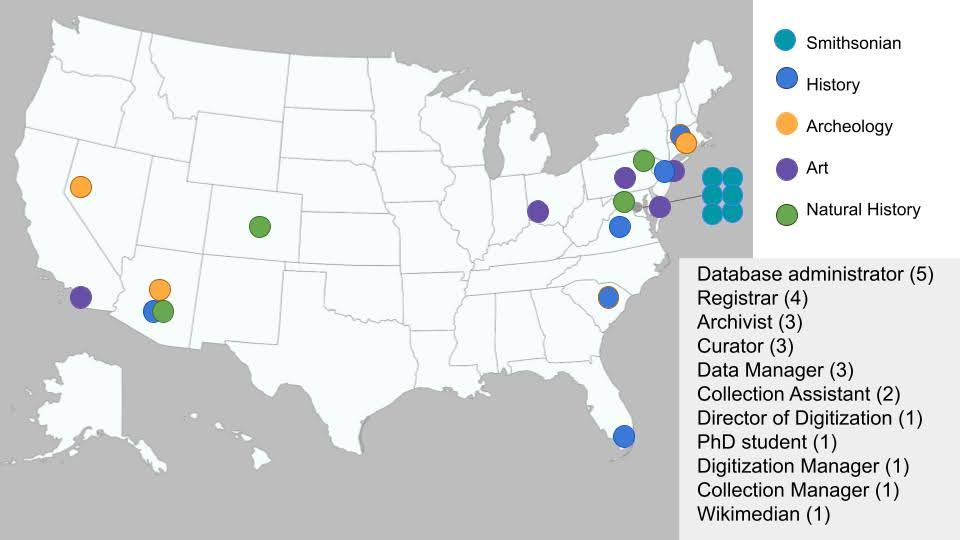

My dissertation research examines the invisible labor of women working in museum collections, and the ways they see their labor as gendered. Over the summer of 2024, I completed a museum studies practicum that explored these questions in museums across the United States through virtual interviews with practitioners. I spoke with individuals across a wide range of museum collections, including art museums, natural history and science museums, history and archeology museums, and large multi-institution sites like the Smithsonian. Removing the focus on one type of museum was in a goal to highlight that this gendered work is not specific to any one type of museum, or museums with a certain budget, but instead, a pervasive issue that permeates museum work as an entire field.

Museums are a unique labor environment. Overall, museum work is a feminized profession, with the majority of work done by women. In 2022, the Mellon Foundation estimated that 61% of museum professionals are female. The museum world follows trends in other ‘pink collar’ professions—like nursing, child care, and teaching—of stagnant pay and limited upward mobility. Museum work is a clear example that women having representation in the workforce does not equate to power or equality in work environments, as I unpack further in this post.

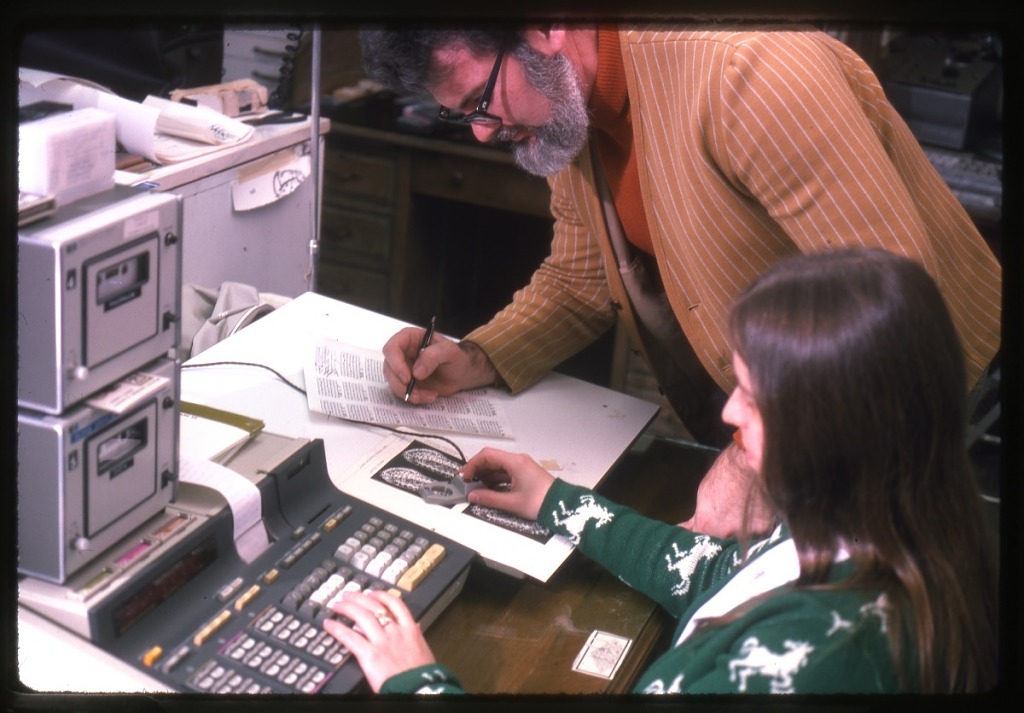

Gender plays a central role in the digitization of museum work: when computers were initially brought into museum collections as inventory, cataloging, and record-keeping tools, many museums relied on the invisible labor of women trained as typists and keypunchers to input data into these new systems. These women were not seen as part of the knowledge-production process and were given little credit for their work. Further, they were often hired in short-term contract positions.

These keypunchers and typists are some of the first workers in museum computing—a specific type of museum work I explore in depth in my dissertation. Museum computing is a set of collection-centered tasks that disseminates the knowledge of a museum collection into a digital medium. Today, museum computing largely consists of individuals working with massive amounts of collection data, including tasks like adding records to museum catalog systems, data cleaning, data curation, coordinating data sharing with large-scale data repositories, and managing digitization projects. Early museum computing work practices have set the foundation for what museum computing looks like and continue to have lasting impacts on the experience of women museum workers today, even though the work tasks have become increasingly complex and require skilled expertise.

Interview Findings

To better understand the impacts of this gendered museum work today, I interviewed 24 women—all participants were given the choice to self-identify their gender and chose “woman”—currently working in museum computing. I identified two themes in the the way that their gender impacts their computing work: firstly, the devaluing of their computing labor in regards to wages, and secondly having to constantly validate their expertise with external collaborators.

Summary of the women I spoke with, including the location and type of museum they worked at, and their job titles.

Wages

Museum work is a largely low-paying profession, especially considering the amount of education and training it requires. Further, these roles can be challenging to break into and often require several internships to lead to full-time work. It doesn’t help that unpaid internships are also often the norm: A 2017 survey from MuseumNext found that 48% of survey respondents had participated in unpaid internships throughout their careers. The experiences of my participants support these anecdotal claims and further highlight that inequality in pay is also present within different departments of a particular institution.

Of the 24 women I spoke with, 17 were in charge of overseeing their collection management database, or one of the main digital systems for their institution. However, many reported they were paid far less than database administrators or data analysts— professionals in adjacent fields who do the same work. One participant stated, “If my role was in a business, I would be a data analyst and that role would be given a lot more clout.”

Even within an institution, collection computing work is valued (and paid in accordance) far less than traditional information technology (IT) work. Another participant stated, “They [management] got a great bargain by putting me in the archives.” She went on to describe that her technical skills are similar to those working in the IT department of her institution. However, her work is not valued in the same way, including by salary metrics. This is a clear example of gendered work, as it was expressed in multiple interviews that those employed in more traditional IT roles in museums tend to be men.

Other participants noted that leaders in their institutions were aware that having words like ‘database’ and ‘manager’ in job titles could lead to conversations about salary, so they simply built that work into other roles and it was informally recognized as their responsibility. One registrar expressed their experience in a similar instance:

I’m the unofficial database administrator. That’s not my official title, but I am the person that the database administration falls onto. I do the vast majority of the data entry for our collections database…I attach all the images. I do a lot of data cleanup… they [museum leadership] seem to understand that database administration is important. And they don’t want to pay a database administrator because they cost a lot of money. So if they can get someone to unofficially administer the database it’s much easier to just pay for some training instead of salary.

This is a clear example of invisible labor: if the work you do is not acknowledged in your job title or description, it remains hard to advocate for its institutional value.

In sum, from the experiences shared by my interview participants, there is a clear recognition that museum computing work is not valued in the same way as other forms of computing labor.

Expertise not taken seriously

A second finding from these interviews is that women have to do an enormous amount of work to be taken seriously as experts in the respective digital systems they manage, both with individuals within their institutions and external contractors they may work with. Many participants shared that parts of their computing work are tied to proprietary collection management systems and that they are the communication point person for developers of these systems who are often employed outside of their institution. Often institutions pay an annual fee for this software, along with one-time fees to assist with large-scale tasks like data migration, or editing the software’s data schema. Communicating with the developers of these systems was a common job task mentioned by interview participants.

A common sentiment expressed in the interviews is that the developers of these systems are usually men and often have stereotypical ‘tech-bro’ attitudes, as one interview subject put it. Multiple interviewees shared that, as women working in these roles, they had a hard time being taken seriously as the experts of their data systems. Further, they had trouble getting their concerns addressed by these point people who had the responsibility to help them maintain the systems for which their institutions had paid.

One woman, who oversees the digital asset management system (DAMS) for a large institution, describes the tension she’s encountered when asking for additional affordances from their system developers. She stated, “If something is inconvenient, or I feel like maybe there’s a better way to do this. I’ve often been met with derision, or ‘you couldn’t possibly know what you’re talking about.’ [The developers] have an outright condescending attitude.”

Another participant, who is a manager for multiple digital systems, expressed a similar experience:

I for sure have experienced not being listened to, or my opinions weren’t considered as correct as others…And I have noticed in my current job, just talking to the users [those entering information into the internal collection management system] versus the IT support, that there’s a huge disconnect. And it’s usually because they don’t understand each other and IT underestimates what the users need. And users, they feel underestimated and they also don’t know how to explain what they need because they feel like they’re not going to be listened to anyway. And it’s largely women versus men. Users are largely women, and IT support is largely men.

Finally, a third participant summed up her perspective simply: “I got the impression that they did not like a woman, especially a young woman, telling them what to do and being really direct about our needs.”

This finding has significant implications: this gendered computing is not only frustrating to the women not being taken seriously in their work, but it also adds unnecessary delays to their work and the operations of their institutions. In future writings on this project, I plan to unpack this further—how gendered computing ultimately limits the possibility of innovating computing work in museums.

The value of labor

The experiences of the women I spoke with are not stand-alone encounters, and shed insight on issues that impact all workers (both paid and unpaid) in the museum field. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated labor issues that have been present in museums for decades, including low wages and precarious employment in an increasingly professional field. It is no coincidence this goes along with a growing movement of museum workers unionizing, often with extreme pushback from leadership and board members. In fact, according to the Art Newspaper, workers at more than 20 institutions have formed a union since 2020, joining the already existing network of museum employees who are members of a labor union.* Labor unions are just one way that museum workers are trying to address the inequalities they face in their work, but overall speak to a larger trend of cultural heritage workers who are advocating for the work they do.

Image of striking workers at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 2022, members of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) union went on a 19-day strike to combat a myriad of workplace issues, including low pay and poor job security. (Image originally published by LaborNotes.org, November 17, 2022.)

I bring up these issues not to criticize our institutions, but because I see the immense value that museums hold as cultural keepers in society. However, the legacies of these institutions are directly tied to their workers who carry out their missions every day. Understanding the experiences of workers, and the shortfalls of the labor systems they operate within provide insight on how we can do and fund museum computing better.

The research conducted during my practicum has served as the first study in my dissertation research. Specifically, after spending months conceptualizing this project, the practicum was my first chance to speak to practitioners about how they see their work as gendered. The topic of this blog—that museum computing is indeed gendered—is still a surprising finding to me. Not that museum work is gendered, but that the participants I spoke with could so clearly define the ways that their computing labor is gendered and provide salient examples. Since concluding this interview study, I have begun archival research at two museum collections to unpack early conditions of museum computing labor and to amplify the work of these early typists.

* It is challenging to find exact numbers of the number of museums nationally that have formed labor unions, but the list includes the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met); the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), the Museum of Tolerance, the American Museum of Natural History, Milwaukee Public Museum, the Detroit Historical Society (all part of the parent union AFSCME); Milwaukee Art Museum; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Portland Museum of Art, Maine; Meow Wolf, Santa Fe; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Film at Lincoln Center and Poets House, New York are among some unionized museums.

For further readings on this topic, I recommend looking into these books and articles which this post draws from:

- Baldwin, Joan H., and Anne W. Ackerson. 2017. Women in the Museum: Lessons from the Workplace. First edition. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Callihan, Elisabeth, and Kaywin Feldman. 2018. “Presence and Power: Beyond Feminism in Museums.” Journal of Museum Education 43 (3): 179–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2018.1486138.

- Nie, Taryn. 2017. “‘Far Too Female’: Museums as the New Pink-Collar Profession – An Introductory Analysis of Pay Inequity within American Art Museums.” Seton Hall University. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2315/.

- Parry, Ross. 2007. Recoding the Museum: Digital Heritage and the Technologies of Change. Museum Meanings. London, New York: Routledge.

- Turner, Hannah. 2020. Cataloguing Culture : Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. UBC Press.

Alexandria Rayburn

Alexandria Rayburn is a doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan School of Information, where she also received her master’s degree in Information Science. She conducts qualitative research on topics related to computing in museums and knowledge infrastructures. Specifically, she studies the data practices and labor required to maintain these systems. She has published in Archival Science, Science Technology and Human Values, and more.